OUR MISSION

Understanding the environmental responsiveness of plant epigenomes

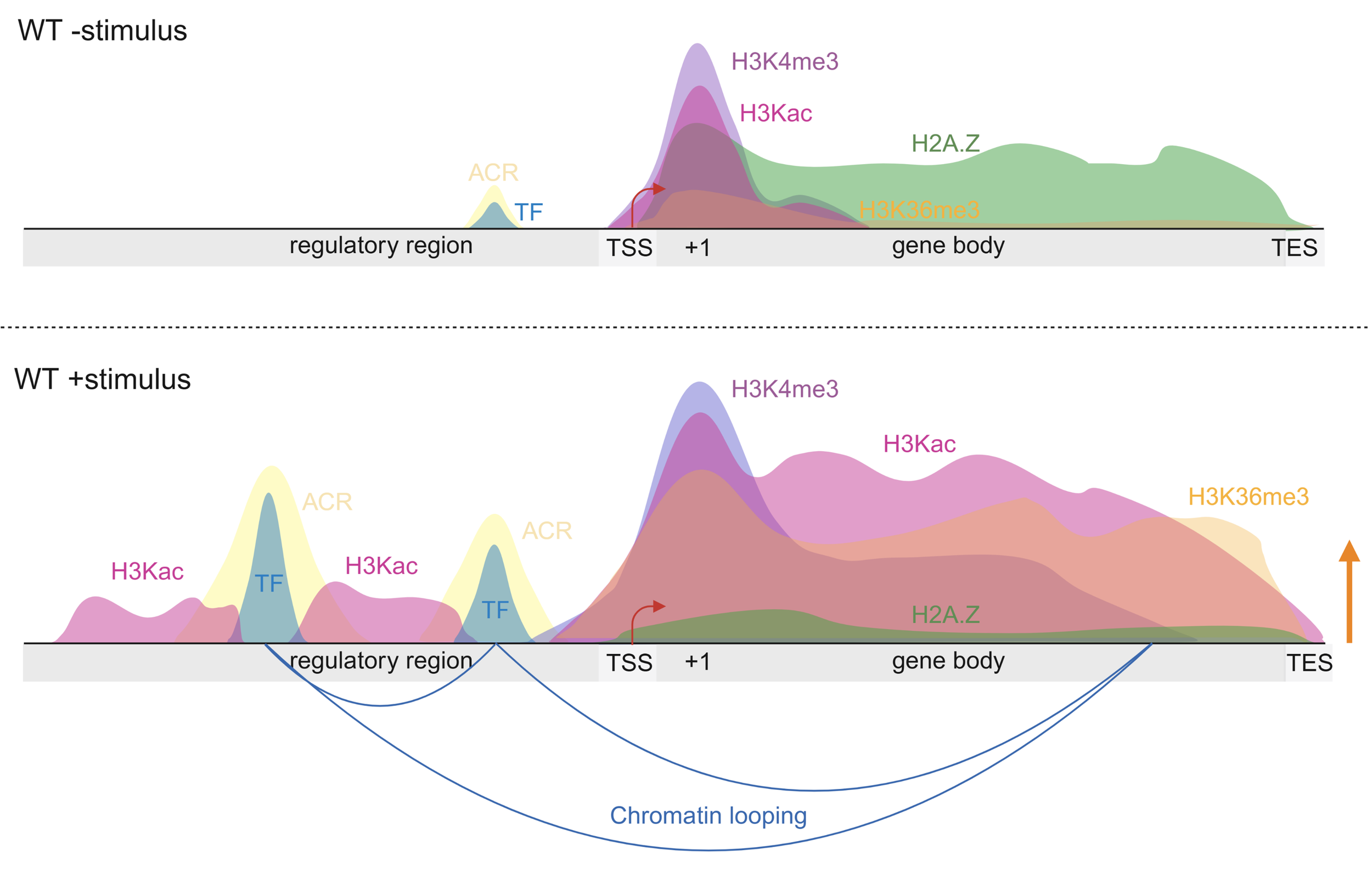

The integration of environmental cues into gene regulatory networks (GRNs) is fundamental to plant adaptability and survival. Central to this cue-dependent integration is the epigenome, which comprises chemical modifications of chromatin - including DNA methylation and post-translational modifications (PTMs) of histones - along with chromatin accessibility, three-dimensional (3D) chromatin organization, and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs). In response to environmental cues, the plant epigenome undergoes extensive reprogramming as an integral component of cue-induced transcriptional responses (Figure 1). This environmental responsiveness is essential for achieving spatiotemporally precise gene regulation, and elucidating its underlying mechanisms is critical for deciphering the molecular logic governing plant-environment interactions.

Figure 1

The Zander Lab focuses on transcription factors (TFs), which act as key architects of the environmentally responsive epigenome. TF binding to DNA is frequently triggered by cue perception through diverse molecular mechanisms. Once bound, TFs act as recruitment platforms for a wide array of chromatin regulators (CRs), including chromatin remodeling complexes as well as histone and DNA modifiers. Although the general framework of cue-induced, TF-mediated epigenome reprogramming is widely accepted, the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood due to their immense complexity. This complexity stems from the large number of interacting components, including more than 1,500 TFs per plant species, hundreds of CRs, dozens of epigenome features, and the multitude of environmental cues and cell types.

To dissect this regulatory complexity, the Zander Lab employs a broad suite of genetic and genomic, but also proteomic approaches to address fundamental biological questions.

What is the exact function of environmentally responsive epigenome features?

How do TFs confer responsiveness to plant epigenomes, and how can these functions be manipulated?

How can we advance existing genomic tools and develop new approaches to enable robust multiomic analyses across a broad range of plant species?

RESEARCH AREAS

Jasmonate-induced epigenome dynamics

We use the responsiveness of the epigenome to the plant hormone jasmonic acid (JA) as an experimental system to investigate general principles by which plants integrate environmental cues into their epigenome. JA is synthesized in response to wounding, pathogen infection, and herbivory, and is perceived on chromatin in its bioactive form, JA-Ile, by a co-receptor complex composed of the F-box protein COI1 and JAZ repressor proteins. Master regulator of the JA signaling pathway is the basic helix-loop-helix TF MYC2 and its close homologs MYC3, MYC4, and MYC5.

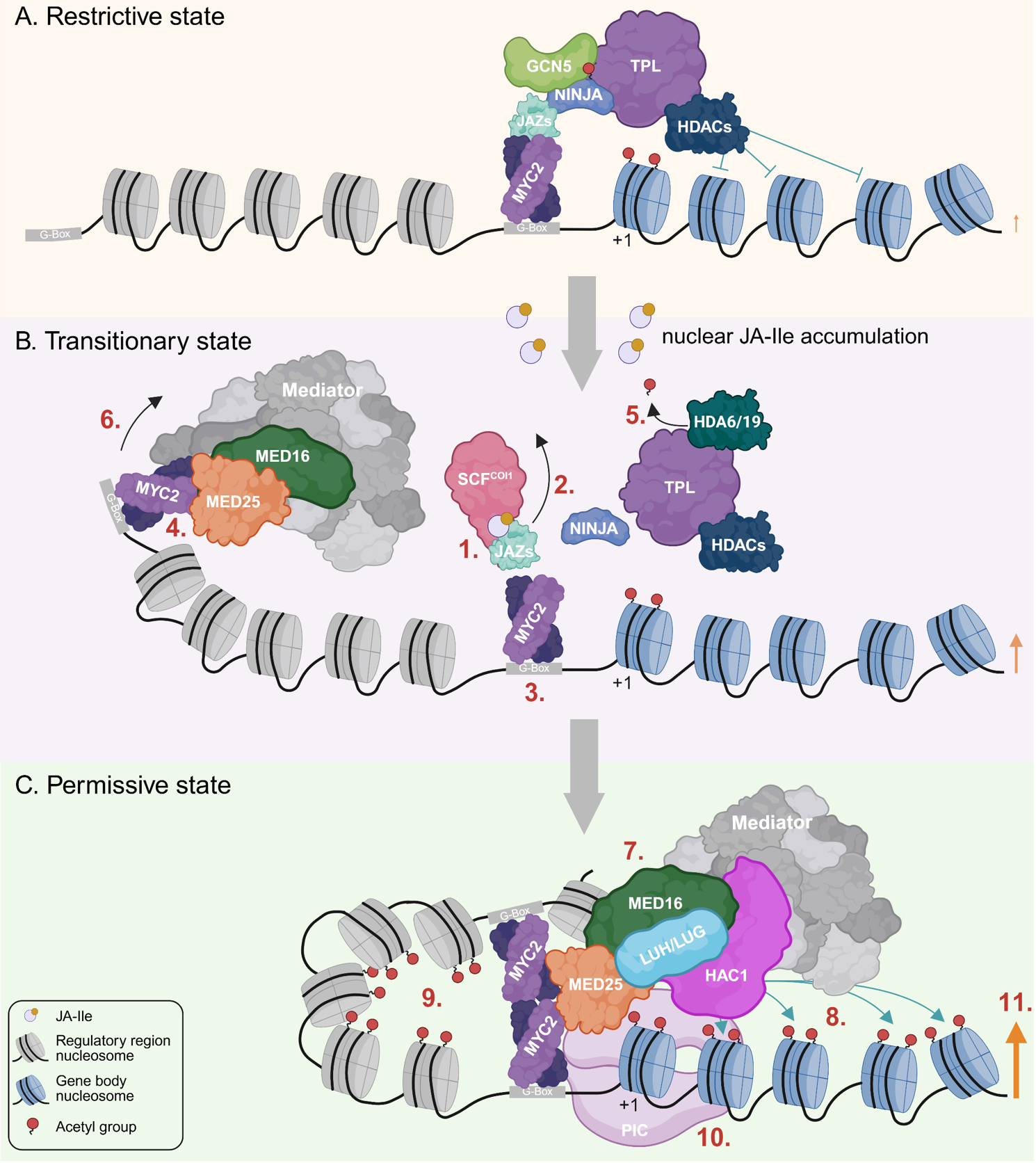

Figure 2

Current models propose that JA-Ile levels determine the composition of chromatin regulator complexes associated with MYC2, thereby shaping the histone acetylation landscape at MYC2 target genes. In the absence of JA, MYCs associate - via the JAZ-NINJA adaptor complex - with the repressive TOPLESS (TPL) corepressor complex, which comprises TPL/TPR proteins, and histone deacetylases (HDACs), to keep histone acetylation levels at MYC2 target genes low.

Upon JA-Ile perception and subsequent degradation of JAZ repressors, MYCs instead associate with the permissive MED25 complex, which promotes histone H3 acetylation and consists of MED25, a subunit of the Mediator complex, the histone acetyltransferase HAC1, and LEUNIG and LEUNIG_HOMOLOG (Figure 2). (Big credit to the groups of Chuanyou Li, Roberto Solano, Gregg Howe, Alain Goossens, John Browse and many others). Find our recent review on the JA-responsive epigenome in New Phytologist here: https://nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nph.70865.

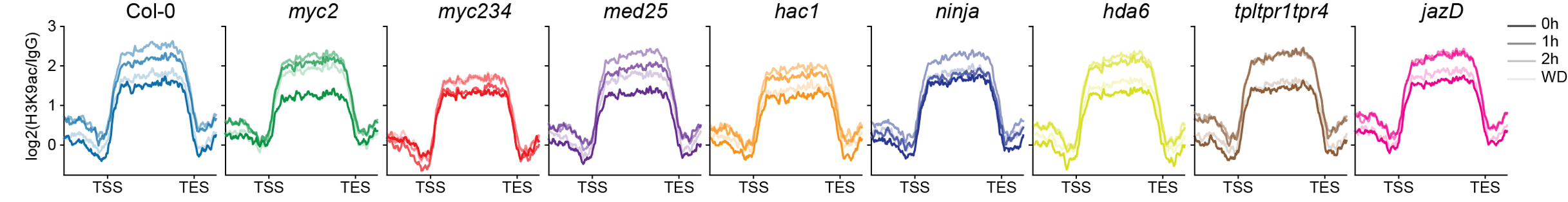

Although very elegant, the current model remains incomplete. We recently developed PHILO ChIP-seq, a high-throughput ChIP-seq platform, which we used to assess JA-induced H3K9 acetylation dynamics in Arabidopsis Col-0 and eight JA pathway mutants.

While myc234 mutants were largely impaired in establishing a JA-responsive H3K9ac landscape, most other tested mutants showed only marginal effects (Figure 3), indicating the presence of additional, currently unknown components that we are actively working to identify.

Figure 3

Technology development to facilitate genomics-driven plant research

Studying TF-mediated epigenome reprogramming requires a comprehensive suite of genomic tools capable of capturing a wide range of epigenomic features at a genome-wide scale. In addition to DNA methylation profiling by MethylC-seq and chromatin accessibility mapping by ATAC-seq, the occupancy of histone marks and variants, RNA polymerase II, as well as the DNA binding of TFs, cofactors, and chromatin regulators can be interrogated using ChIP-seq, CUT&RUN, and CUT&Tag. Although most of these methods can be applied to plant species with reasonably well-assembled genomes, mapping TF cistromes - the complete set of TF DNA binding sites - remains challenging due to the limited availability of high-quality antibodies for plant TFs. Consequently, TF cistrome profiling often relies on epitope-tagged TFs. This limitation can be bypassed using DAP-seq, an in vitro approach in which recombinant, tagged TFs are incubated with genomic DNA, and TF-DNA binding events are captured and sequenced.

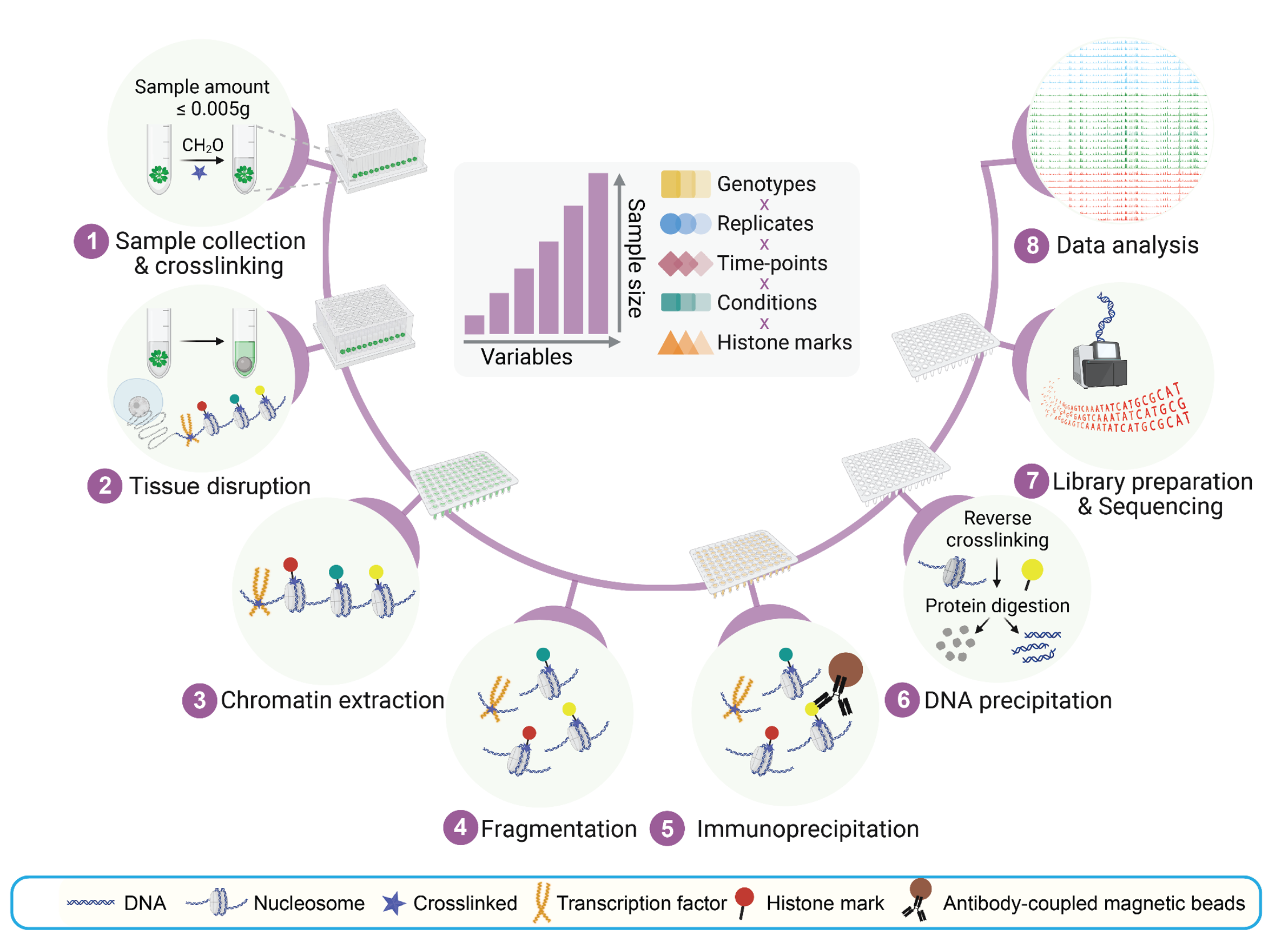

Figure 4

Despite the availability of these tools, numerous limitations remain, including high costs, limited scalability, restricted multi-omics capabilities, and poor accessibility for crops and non-model organisms. Our goal is to overcome these challenges by advancing and tailoring existing genomic tools for use in plants, as well as by developing new methodologies. We recently developed PHILO (Plant High-throughput Low-Input) ChIP-seq, a high-throughput ChIP-seq platform that enables cost-effective profiling of TF cistromes and histone mark occupancy in more than 100 samples in parallel (Figure 4).

More details can be found here: https://academic.oup.com/nar/article/52/22/e105/7908794